Wanna be amazed by some facts?

Simone Gillardoni was our third lecturer and it was good. He had a great start. Check on this link:

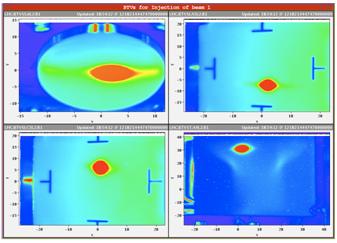

This screen is the real one on real time. Imagine that you are a great physicist or top engineer and you are working for CERN. This is what you would see on the control room, the same exact screen. As you can see now they are on SHUTDOWN TWO (LS2), years 2019-2020, so the screen is pretty boring. They are preparing everything for the next run and for the high luminosity LHC (I will explain it in another entry, wait for it) and everything is turned off. But if you check the same website in 2021 you could be able to see what it is happening on real time, day and night. Isn't it cool?

Now, let me give you some amazing facts:

1) LHC works at T = 2K, that is a super cool temperature (remember about the absolute temperature scale? Well, it is super close to 0 K), so they have to increase the temperature to 298 K (25 ºC) for people to be able to work down there. They do that temperature raise in a super slow way so they do not break any materials, that takes them two months to heat the system up. And that explains why the shutdowns last years, they need so much time to change anything.

The magnets in the LHC are superconducting, i.e., they have almost negligible electrical resistance. For this to occur, they have to be cooled to about 2 deg Kelvin, i.e., -271 deg. Celsius, or -455 deg. Fahrenheit.

By studying the Cosmic Microwave Background, which is a form of electromagnetic radiation filling the universe, astronomers have deduced that the current temperature of the universe is about 2.7 deg K.

Some experiments in solid state physics laboratories operate much closer to absolute zero, e.g., at 10-6 Kelvin, so we cannot claim that the LHC is the coldest place in the universe, but it certainly is one of the coolest (in more ways than one!).

2) The LHC can operate at 8 TeV (but they do not make it work at its maximum), anyway, we will use this value for our calculations.

When operating at design parameters, the LHC will have two beams of protons, where each beam consists of ~2800 individual bunches, and each bunch contains ~1011 protons. Each proton will have energy of 8 TeV, so the energy of each bunch of protons is ~ 8*1011 TeV, i.e., 133,000 Joules (or 133 kilo Joules).

The LHC collides two beams of protons, each with energy of 4 TeV. If you were standing at the collision point, you would feel a total energy of 8 TeV, but you would not have moved in any direction. In contrast, if you were to be hit by only beam, you are likely to fall backward. Each beam contains 1011 protons aproximately. Substitute a moving car for each proton in the proton beam, and you will see what I meant! OK, so can you make yourself an idea?

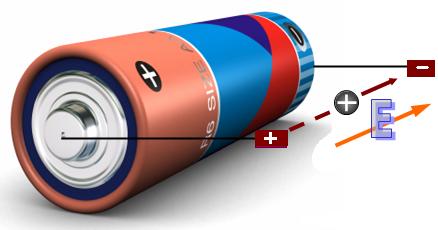

Please look at Wikipedia for a discussion of units. Briefly, 1 Joule is the energy of a 1 Kilogram mass moving with a speed of 1 meter/second (1 J = 1 Kg * (1 m/s) 2). In particle physics units, it is equal to about 6*1018 electron volts, i.e., 6*106 TeV (1 T(era)eV = 1012 eV). It is time for you to understand how a battery works (this is your homework):

Do you need another analogy? If we use the energy provided by an old TV, and knowing that every TV can give us an energy of 20 keV, we would need 350 millions of TVs connected to obtain the same energy, therefore you will have a line of TV machines around the Ecuador of the Earth.

Still don't get it? A bullet fired from a rifle typically weighs 4 grams, and is travelling at about 1000 m/s when it leaves the barrel. This corresponds to a kinetic energy of about 2000 Joules, or 2 kilo Joules, i.e., roughly 1/66 the energy of one bunch of protons. Anti-tank shells (used in WW II) had energies anywhere from 150-800 kilo Joules. So it is crucial that the beam does not hit something that it is not intended to hit! (BTW, I have not included the energy stored in the magnets, which is a whole different story, and is many times larger).

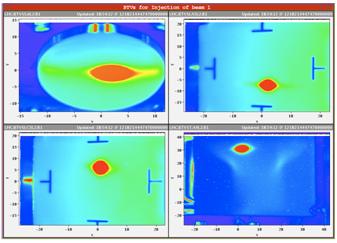

Look at the beam inside the pipes:

2) How about those magnets?

To keep the proton beam circulating at 7 TeV, we need very strong magnetic fields to essentially keep the beams in the circular ring. For this purpose, the LHC has 1232 dipole magnets. Each of these magnets is 14 m long, weighs about 35 tons, and the required magnetic field is generated by passing about 11700 Amps of current through 5 Km of superconducting wire.

Then there are about 7066 magnets that focus the beam, and otherwise correct the path of the proton beam. For instance, if nothing was done, a proton will “fall” down due to gravity after traveling a mere 850 times around the ring (in one second, a proton goes around the ring about 11000 times). In just one second, a proton can take 11 000 laps to the ring. wecan generate 600 millions of collisions per second. Isn't it crazy?

To learn more about the LHC, please take a look here and at the links therein.

¿Quieres alucinar con algunos datos?

Simone Gillardoni fue nuestro tercer ponente y fue bueno. Tuvo un comienzo alucinante. Mira este enlace:

Esta pantalla es la de verdad. Imagínate que eres un gran físico o un ingeniero y estás trabajando en el CERN. Esto sería lo que verías en la sala de control, la mismita pantalla. Como puedes ver se encuentra en un parón técnico número 2 (LS2), desde 2019 a 2020, así que lo que se ve es bastante aburrido. Actualmente se encuentran preparando y reparando todo para la siguiente puesta en marcha y el acelerador de alta luminosidad (ya explicaré esto más adelante, tenéis que esperar un poco, que no me da la vida para todo) y todo está apagadito. Pero si entráis en el enlace durante 2021 podréis ver qué estará sucediendo en tiempo real, día y noche. ¿Mola, eh?

Ahora voy a daros algunos datos muy interesantes:

1) El LHC (colisionador de hadrones) trabaja a una temperatura de 2K, eso es súper frío (¿os acordáis de la temperatura absoluta y cómo funciona?), así que cada vez que alguien tiene que ir al túnel a trabajar tienen que aumentar la temperatura hasta 298 K (25 ºC) para que la zona sea habitable. Para poder hacerlo, el incremento debe ser progresivo y de manera lentísima para no romper los materiales de los que está hecho los cables, cavidades, tubos, imanes, etc. Aproximadamente tardan unos dos meses en calentar el sistema. Esto explica que el parón técnico dure años, en general se necesita mucho tiempo para cambiar cualquier cosa.

El LHC está tan frío porque trabajamos con superconductores, que prácticamente no presentan resistencia al paso de la corriente eléctrica. La única pega que tienen es que trabajan a temperaturas bajísimas (2 K = -271ºC).

Al estudiar la Radiación Cósmica de Fondo, que es una forma de radiación electromagnética que forma parte del Universo, los astrónomos han predicho que la temperatura del Universo es más o menos 2,7 K.

Algunos experimentos que se realizan aquí se dan a 10-6 Kelvin, así que tenemos el récor, el LHC es el lugar más frío del Universo.

2) Cuando el acelerador está funcionando hay dos haces de protones circulando en sentidos opuestos, cada uno de ellos con ~2800 grupitos individuales, y cada grupito contiene ~1011 protones. Cada protón tiene una energía de 8 TeV, así que la energía del haz de protones es ~ 8*1011 TeV, es decir, 133,000 Julios (o 133 kilo Julios).

El LHC entonces, puede operar con una energía de 8 TeV pero nunca se fuerza la máquina al máximo (pero para nuestros cálculos utilizaremos este valor).

Dentro del tubo del LHC colisionan dos haces de protones, cada uno con una energía de 4 TeV. Si te pudieras colocar en medio del punto de impacto sentirías una energía de 8 TeV pero no te podrías mover en ninguna dirección. Por el contrario, si solo fueras golpeado por un haz, te caerías hacia atrás. Cada haz contiene aproximadamente 1011 protones. Ahora sustituye un solo protón por un coche y te harías una idea de lo que quiero decirte. ¿Cuántos coches te darían? ¿Entiendes la cantidad de energía que tienen 8 TeV?

Te lo cuento de otra manera.Si le echas un ojo a Wikipedia podrás encontrar las equivalencias de las unidades. De manera rápida, un Julio es la energía de 1 Kg de masa moviéndose a una velocidad de 1 metro por segundo. En física, esto es igual a (1 J = 1 Kg * (1 m/s) 2), esto es, 6*1018 electron volts, por ejemplo, 6*106 TeV (1 T(era)eV = 1012 eV). Es el momento de que te intereses por cómo funciona una pila (tienes deberes para casa).

¿Sigues sin entenderlo? A ver, en el LHC cada protón alcanza una energía final máxima de 8 TeV (7 TeV porque hemos dicho que no forzamos). Si utilizáramos la energía proporcionada por un televisor de tubo (si, es un acelerador pequeñito) y sabiendo que cada televisor proporciona a los electrones una energía de aproximadamente 20 keV, harían falta 350 millones de Tv conectados en serie para conseguir la misma energía y todos ellos colocados unos al lado de los otros ocuparían una circunferencia de 40 000 km, es decir, que tendrías una línea de televisor dando la vuelta al ecuador.

Por si seguís flipando, os pongo otra analogía, cuando se dispara una bala de unos 4 gramos con un rifle, esta sale del cañón a unos 1000 m/s. Esto en energía cinética corresponde a 2000 julios o 2 kJ (y esto es sólo 1/66 de la energía del haz de protones). ¿Por qué insisto tanto en esto? Porque es crucial que el haz no colisione con nada que no sea otro haz (o cualquier otro objetivo marcado por el experimento), podría ser desastroso. Pero no, no explotaríamos el mundo (qué daño hace la mala TV). Ya que estamos, no, la Tierra no es plana, sí, las vacunas funcionan y no, cuando tengo un catarro, no siempre necesito antibióticos.

Fijaos que agrupadito va el haz para que no colisione con las paredes de los tubos (imagen real):

3) Oye, ¿y los imanes?

Para mantener el haz de protones circulando a 7 TeV, necesitamos un campo magnético muy potente que haga que el haz se curve en el anillo. Por eso el LHC tiene 1232 dipolos magnéticos de 14 m de longitud cada uno y con una masa de 35 toneladas. El campo magnético generado por los mismos es creado gracias a 11700 amperios de corriente que circulan a través de 5 km de cable superconductor.

También tenemos 7066 imanes que se encargan de reducir o focalizar (¿existe esta palabra?) el haz de manera que su trayectoria puede ser corregida (recuerda la energía a la que viajan, no nos podemos permitir un error). En un segundo, un protón da 11 000 vueltas al anillo. Y se generan 600 millones de colisiones por segundo. Una locura.

Para aprender más sobre el LHC, échale un ojo al siguiente enlace:

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario

Gracias por tu aportación. Verificaremos que no contiene palabras malsonantes o contenido inapropiado y procederemos a su publicación.